This story was first published in The Elastic Book of Numbers (Elastic Press 2005), which won the British Fantasy Award for Best Anthology in 2006.

i

He had it shaved into his crew-cut sometimes, and he had a thing about black t-shirts with i printed on them in large type; people often asked him for the name of the lead singer. I had traced the tattoo above his left nipple with my finger, more than once.

I found him in my bed, the following morning. I wasn’t very surprised; I had barely been conscious towards the end of the party. I sat up and looked at the bare shoulder next to me. Slowly, a memory surfaced: a short chill, a warm weight on the other side of the mattress, a blanket pulled up. “Good afternoon,” I said. “And you are...?”

His shoulder twitched, and he turned over quickly. He blinked, then stared past me, wide-eyed.

I grinned. “Not a pretty sight, I know.” Although I had mounted all computer monitors into steel racks along the side wall, it was still an impressive amount of dusty glass embedded in grey plastic, a backdrop for the yellowed keyboards on the formica tabletop. Only the stacked desktop computers of Heorot — the small Beowulf cluster which was barely a year old but just as unemployed as me — gleamed deceptively within their noise-reducing enclosures, towering on either side of the rack. I had dusted them just the day before.

In the summer midday light filtering through the thin paper covering the two high windows, his head was pale and stubbly. The close-cropped hair above his round face was dullish brown, his eyes more grey than blue. He was probably slightly younger than myself.

The blanket slid off him as he sat up, and there it was: a lowercase i on the pale skin of his chest, executed in careful blackwork, barbs at top and baseline, and dotted with a stylised tear.

I yawned, stood up, winced. Pain in my wrists again.

The bedroom was warm and oppressive. But then, the rent on the flat was low enough for my disability benefit. The renovated warehouse, on a disused industrial estate at the edge of the city, was actually an ex-squat, legalised years ago, but the industrial ambience still attracted a specific type of tenant. The annual house parties in the large ground floor commons were part techno rave, part art happening, too small to draw unwelcome attention, yet big enough to blur certain boundaries. This was not the first time I woke up beside someone whose name I did not remember.

“Ian,” he said.

“Richard,” I said, placing a hot mug in front of him. “Hence that letter on your chest.”

He stared into the coffee. “No.”

“Oh. Okay.” I sat down. “I don’t want to appear nosy.”

He turned his head and looked out of the window. Above the harbour cranes north of the estate, frozen in the tranquillity of a regular Sunday, the air shivered.

“Depressing,” he said.

I grinned. “It grows on you.”

He looked at me. “It’s: that letter on my chest. Hence: Ian.”

I nodded. “Right.” I felt stalked by a Sunday afternoon mood, which would soon develop into a burning desire for solitude. I hoped he wouldn't stay much longer.

“But my real friends call me i.”

“And what is i?”

“Imaginary unit.”

It took me a moment before I understood. “So you’re a mathematician?”

“Composer.”

And I could not resist. “Some people would say that’s the same thing, nowadays.”

“And some people would be right.”

I was silent. Of course I knew about i. No introduction to algebra could do without explaining complex numbers; how a complex number was the sum of a real part and an imaginary part, and how they could be used as an extension to the real numbers, to find the roots of equations that had no real solutions. It was literally an extra dimension: an alternative universe where the square root of -1 equalled i.

But I had never met someone calling himself i. Even at the house party introductions usually exceeded three letters.

So I asked: “Has your work been performed anywhere?”

He grinned weakly. “Do your programs run on actual computers?”

“Not anymore.” Showing him my hands. “Out of order. RSI. My hacking days are over.”

His face darkened. “Sorry.”

I stared out of the window, across steel and concrete, shrugged. “We have to move on.”

“On to what?”

“Good question,” I said. “Where do you live?”

He sipped his coffee, and stared aimlessly in front of him. “Nowhere.” He glanced at me, almost as if he already knew what I was going to say.

I waited for the unreasonable disgust and anger to wash over me, naturally tempered by an immediate and equally conditioned tolerance reflex. But... almost?

So I waited a bit longer, and when the silence had stretched long enough, I asked: “And where is that?”

He looked away and stared outside again. He nodded at the harbour cranes in the distance. “Somewhere beyond there, I think.” He stood up. “Where’s the loo?”

Ten minutes later I discovered him sitting on the floor, scrutinising the titles in my CD collection. One by one he pulled the cases from the shelves and examined the booklets.

“Who’s this?” he asked suddenly. The photo showed an angular face, only half visible, under a thatch of grey hair. One eye stared coldly past the camera, the other was hidden in a darkness of furrows and twisted shadow.

“Xenakis,” I said, lifting an eyebrow. “Don’t tell me you’ve never heard of Xenakis? You should recognise the most interesting composer of the twentieth century!”

He smiled. “Not where I live...”

“Where was that again?”

Slowly he put the CD back. “On the imaginary axis,” he said quietly, without looking up. “North of reality... Our greatest living composer has a different name. You wouldn’t know her, I think.” Suddenly he turned his head and looked at me, beaming. “But I should be nice to you. You’re a music lover, with a fast computer into the bargain.”

Smiling weakly, despite my still growing uneasiness, I said: “Would you like to be introduced?”

Only when he flawlessly reeled off the parameters of a Mandelbrot fractal fluttering in colourful bifurcations across the cluster’s main screen, I realised that it was growing dark outside. We had filled up the afternoon with computer time, and I had forgotten the actual time; obviously, there was that about him which fascinated me. I had never met someone with the ability to describe the boundaries of a Mandelbrot subset, accurately, after just one look. Naturally the term idiot savant occurred to me then, and I looked at him warily.

He was staring at the MIDI keyboard resting against the wall next to one of Heorot’s system stacks. “Do you play music?”

I shook my head and showed him a limp hand. “Not anymore. I’ve sold the piano, but I’d only lose money on that synth. So I’ve kept it, for now. I listen a lot, these days.”

He walked up to it and inspected the controls. “Is it connected to anything?”

Later I sat on the bed in twilight, leaning against the wall and staring at his slender back, bent and diminutive in front of the MIDI keyboard now standing between Heorot’s towers. Slowly I nodded off.

And the music started.

I leaned forward and fell. Birds the size of ships sailed past below me, emitting deep bass tones in incomprehensible staccato Morse code.

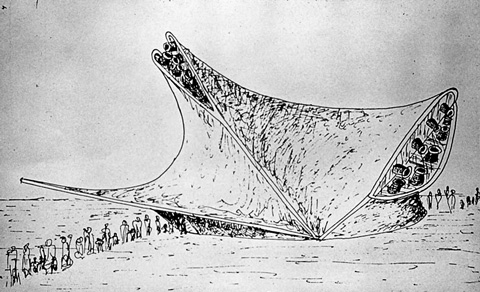

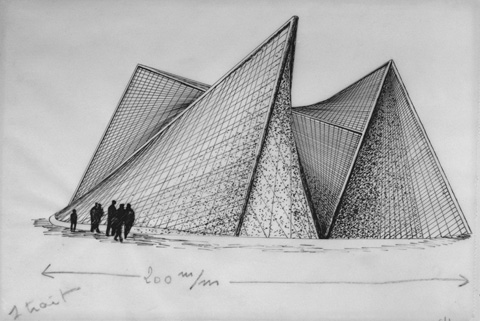

A building shaped like dozens of hyperboloids, flexed around each other, generated dense music full of percussion and wrenching microtones.

A dead plain filled with silence like ice. Harsh rocks...

I came awake with a start. Somewhere in the warm dark a monitor flickered. Through the half open door, a band of dim light fell across the floor.

I sat up. “Ian?”

The composer is crouching behind the piano. Outside: dry cracks of mortar grenades and the rattle of machine-guns. There is no glass in the window closest to him, and several slats are missing from the roll-down shutter. The winter morning chill is laced with the sharp smell of gunpowder, and he has to suppress a persistent urge to sneeze. His tongue feels dry. The reservoir has been empty for days, and the water is strictly rationed.

The composer is trying to find a pattern in the sound of the detonations. He taps distractedly against the barrel of his rifle — a metre in the chaos of shots. Every time the pattern starts to form, a crash somewhere disturbs it. And every time, just when he thinks he has it, it slips out of reach.

Somehow he feels that he should not be here, that he has been removed from the regular course of things, and dropped randomly into a related but not entirely causal thread of events.

He sneezes.

Across the room, Yorgos is sitting next to the machine-gun underneath another window, binoculars in hand, intently peering outside through the half-closed curtains.

And Manolis.

Manolis is lying slumped against the back wall with his eyes closed, pale, one arm across his chest, one hand pressed against his side. His forehead is beaded with sweat, despite the cold. Every time he exhales, his chest produces a wet burbling sound.

The composer pushes his head hard against the wooden edge of the keyboard, and closes his eyes. Manolis. By courtesy of the British. Arrogant, meddlesome Britain. Because Hellas, of all places, had to be the next victim of their damned imperialism. Not content to get rid of the Jerries and the pasta munchers, they were now going to define the shape of post-war Hellas. Those...

Stop that! He cuts the familiar litany short. Clenching his jaw, he opens his eyes and stares at the dullish black wood of the piano.

But... the Union Jack flying over the Parthenon! He clenches his fist and hits the side of the keyboard.

Yorgos looks his way.

The composer waits motionlessly until the hollow boom has stopped vibrating through the piano, shakes his head and lowers his hand. “Skata.”

Yorgos points at the window, and says softly: “No Brits, out there.”

The composer nods. Another British trick. “Indians, according to the paper.” He motions at an old Rizospastis lying on the table next to the door. “Mercenaries.”

Yorgos shrugs. “No mercy for those without principles.” He grins wryly. “Objections, comrade Plato?”

Manolis slowly turns his head, tries to clear his throat and coughs. “No...”

Yorgos casts a worried look over his shoulder. “Mano, you shouldn’t —”

“Nepal,” Manolis rasps. “My father met one —” He coughs up red phlegm.

“Calm down, lad. No need to talk. Eirini will be here in a minute.”

“... long knives. Butchers. Watch out.”

Stepping into a chaos of dark organ tones. Complicated and rapid melodies swirling around each other, punctuated with dissonant chord clusters, as if Bartók and Berlioz had conspired to create the most realistic representation of a thunderstorm, casting it into a rhapsody of inhuman virtuosity.

Ian was sitting in the dark again, bent over the MIDI keyboard. Two monitors in front of him formed the only light source.

I put a hand on his shoulder. “Beautiful,” I said.

He shook his head.

“Yes.” I squeezed his shoulder. “I think it is.” I took off my shoes and sat down on the bed with crossed legs.

He had been here for only a week or two. Officially I was a solitary introvert, yet Ian had not left after that first Sunday, despite all unframed questions.

And I had accepted him. As a sort of artist-in-residence, Heorot’s first real user, and as a wise fool, unworldly and naïve. And of course as a lover, because a man is never too old to disregard lessons once learned.

When the music stopped he turned to me. “Why was that beautiful?”

I fell backwards onto the bed and laughed. “Beats me, mister. No accounting for taste, okay?”

He kept looking at me.

“Okay,” I resumed, and sat up again. “It reminded me...” I closed my eyes and continued slowly. “It reminded me of... a grand palace... baroque, decayed. Big rooms full of mouldering and broken furniture, rusty mirrors on the walls. Grey wainscoting, covered with decorations, so you can’t even see where the wall stops. High, blackened ceilings. Dull and dusty chandeliers. Mouldy damask. And from outside, out of an untidy park littered with brown leaves and mossy stone, a weak and greyish autumn sun shines in. You’re standing before the window, and you feel the weight of centuries... Thick and composted into a black mass full of new possibilities.” I opened my eyes and looked at him. “And in the distance, you hear rumbling.”

But in his eyes, incomprehension. “All of that? A palace?”

I nodded.

“And that was beautiful?”

“Wasn’t it?”

He turned away, and stared at the MIDI sequencer on-screen. “I don’t... know, really. Never thought of it that way.” He adjusted some parameters, and restarted the music. “But the sound is okay. Did you know that if you remove the attack from a bell tone, you get something like a pipe organ? That’s what you’re hearing now.”

I nodded slowly, and pointed at the other screen. “What about that?”

He pursed his lips. “Working on a program to calculate i.”

A joke, I thought. “That’s right, the composer is the mathematician...” But he was peering intently at the screen. I frowned. “But Ian, the imaginary unit is... just that. It’s imaginary. A convenience, nothing more. A symbol, defined as the square root of minus one. Trust me. I’m the programmer.”

He smiled and looked at me. “And I’m calculating it.”

I was silent.

Why not calculate 1 for an encore? But it was too late now. He lived somewhere he called nowhere; I had accepted that without question. And he called himself i. No sense now in explaining the meaningless of ‘calculating’ it, was there?

He knew that.

So I asked: “And once you know the result?”

He stared at the keyboard. “A theory of harmony based on complex numeric relations...”

I shook my head, stood up, switched on the light. “Bollocks, Ian. You’re a composer, right? You know that harmony is based on natural ratios. The octave, the fifth, the fourth, ordinary fractions, real numbers.” I gestured wildly. “But a complex number is the sum of a real part and an imaginary part.”

He crouched in his chair, gazing silently past my shoulder, picking his lips.

I shook my head once more. “In music, Ian... how can you have a harmonic ratio with an imaginary component?” I turned around. “Anyway, I’m off to bed.” I walked to the bathroom.

He came after me and grabbed my arm. “Richard...?” He looked at me with a frown on his face and genuine confusion in his eyes. “In music, Richard... how can you hear a palace?”

The first time I let him listen to Boulez, he was deeply impressed. Sitting on the ground, eyes closed, he listened to the terse piano virtuosity of Structures hammering away. Afterwards, on the keyboard, he faultlessly reproduced Messiaen’s tone series on which the piece was based.

I was in the kitchen, standing before the window, looking out, and I shivered when I heard him play it. A bank of clouds shaped like a truncated pyramid was forming in the sky above the harbour cranes in the distance, grey and red in the evening light. I blinked — and the clouds were gone. I kept looking, but they didn’t return.

Later I let him hear a piece by Stockhausen, and by way of compensation, Xenakis’ Pithoprakta. The mathematical and physical systems Xenakis’ works were based on made his eyes sparkle, and he did not want to come to bed before I had pointed him to some formal analyses of the music.

But he was muttering disappointment as he crept between the sheets. “... all so sloppy,” I caught, half waking. He turned to me. “So much coherence, but it’s all wasted on those musicologists. Do they actually know what mathematics is?”

“I guess most of them don’t,” I mumbled. “G’night.”

And the music started again.

A dead plain filled with silence like ice. Harsh rocks, sticking up out of black sand.

A divided city in winter; white columns in ruins of crumbled marble, high and proud on a rocky hill.

A man, walking hurriedly through narrow and steep alleys, searching between lifeless bodies...

And again I woke up. Ian’s face was hovering over me, worried and sweating in the warm early morning. Behind him I saw blue flicker where strings of numbers were scrolling down a screen. Pain in my wrists, again. I moaned and looked at him. “Still calculating?”

He nodded. “Asymptotic approximation. No exact result, of course. But once I’m close enough, perhaps I can use pattern recognition on the partial results... and then...” He caressed my shoulder, but I moved away. He looked at me wide-eyed.

“Sorry.” I shook my head and pulled him close. “I just don’t understand what you’re doing. Why...” My hand covered the tattoo on his chest. “Why don’t you focus on your music? Much more worthwhile, if you ask me.”

I felt his breath against my ear. “What do you think I’m doing? Where I live, i is what you call 1. It’s the unit all musical ratios are based on. If I know the value of i here, I can create a new kind of music.”

I closed my eyes. “As if music is nothing more than calculation...”

“Sound is a computable physical phenomenon.”

“You’re hopeless.” I shook my head and grinned. “We should go to a concert together. You know, Xenakis once defined music as the expression of human intelligence by means of sound...”

“Proves my point.”

“... and he added: intelligence in the broadest sense. Not just pure logic, but also emotion and intuition.”

A while later, he said softly: “One of our composers writes at the top of all her scores: What emotions in air vibration? I...” He fell silent.

I looked at him sideways. “Yes?”

“I’ve always wondered why. But now I’m beginning to see the necessity.”

In the cold basement they sit huddled together around a single paraffin lamp. Something scurries somewhere in a dark corner. Mrs Kyriakopoulou grasps the composer by the elbow and looks at him, two anxious eyes in a face pale with weariness. “How long do you think it will last, boy?” Her two small sons are lying bundled up against the wall next to her. He hopes they are asleep. “Will there be another famine?”

He tries to reassure her: no, no, ’42 is long gone, and the Germans pulled out months ago, remember? Athens is almost ours, we only have to convince the British. But until then, it’s safer underground. And tomorrow will be the New Year!

He still does not know how to tell her that her husband’s company has been overrun by the government army on the way north.

And he does not know if that is still true here, or if it was snipers of Group Khi. Or those louts of the Security Battalions. Or maybe even the police.

But her neighbour, old Kostas Petalas, who is sitting, bent and with his elbows on his knees, in the chair they’ve carried downstairs for him, mutters: “Except there’s no way we can win from them, is there? If they’ve chased out the Germans... What can we do?”

The composer sits down on his haunches, next to him. “There’s only a few of them here. They’re holding the city centre, but Hellas is ours. It’s only a matter of time.” He grabs the skinny shoulder. “Besides, it’s us who chased out the Germans.”

The old man looks at him. His mouth is trembling. “How old are you, boy?” he asks.

The composer feels vague annoyance. As if his age made him less trustworthy! But he decides not to exaggerate. “Twenty-two.”

The man drops his chin to his chest. “You play the piano beautifully,” he says quietly.

The composer laughs, surprised. “But that wasn’t me. That was a friend of mine. He writes music himself. Which I try to, but I don’t study...” He falls silent, embarrassed.

“Debussy, wasn’t it? Your friend plays well. And what do you study?”

“Civil engineering. At the Polytechnion.”

“Then you are well-equipped for a composing career.”

Confusion. He has had so little time for music over the past year. The Resistance and the Party have swallowed him whole. But the music has not forgotten about him — in early morning dream visions after studying late, when the drawings of his Structural Design assignment detached themselves from the paper, to hang above his pillow as sandblasted metal sound sculptures in three imaginary dimensions, deafening. He knows, intuitively, the old man is right, but how can he trust the judgement of an outsider?

“How do you mean?” he asks.

Very slowly, a smile appears on the man’s face. “I’m just a maths teacher. I don’t lay claim to extraordinary wisdom. But I know about Johann Sebastian Bach; he’s the house composer of number theory. But modern algebra needs a new music. The things Bach did with natural numbers... the modern composer should do them with irrationals. Or even with complex numbers.” He gazes in front of him, and folds his hands. “I would so much like to hear a Toccata and Fugue in i.”

But we didn’t attend a concert until months later. There was a premiere at the modern performing arts complex in the city centre, and he asked me to shave his i into the hair on the back of his head, for the occasion.

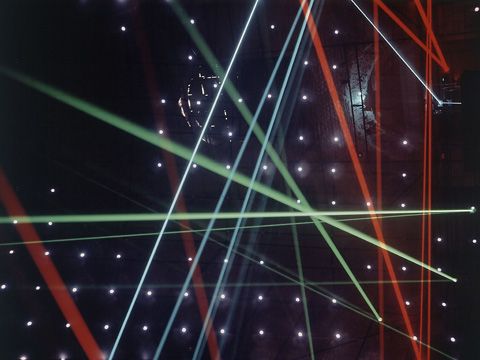

Xenakis’ piece was the last on the programme, and by then of course the house was only half full. The work started with a powerful trombone blast, transforming into a continuous tone in the wind section. The sound seemed to resonate across the hall, rolling from wall to wall, now fading, then blown to full strength again, ricocheting between floor and ceiling; one call with the warm glow of brass, thrown back and forth between trumpets and horns and trombones — before suddenly fanning out in a widening tone cluster of violins and cellos, like a silk thread unravelling in dozens of single fibres.

A few minutes into the music, Ian nudged me, pointing at an opening in a side wall of the balcony.

I shook my head distractedly. “Don’t know,” I whispered. “Control booth maybe. Let’s listen, okay?” But his gaze kept wandering to the doorless opening. Eventually he stood up and walked towards it. He was back a moment later, shaking my shoulder. To avoid the annoyed glances of the typical avant-garde audience, I shrugged in resignation, got up and followed him.

The opening, close to the balcony’s back wall, was about half a meter wide. It looked like an entrance to a maintenance corridor. The walls were bare concrete.

Slowly he stepped through, with me close behind, unwillingly; then a sudden moment of dizziness as the music, complicated and loud now, with lots of percussion, seemed to follow, flowing past and around us into the corridor, filling up the way ahead with whorls and eddies of atonality.

Then, we followed the music. We continued walking along the corridor, and eventually entered a maze of tunnels, shafts and pathways. We walked unnoticed past dressing rooms and stage traps. No one stopped us as we went down into the orchestra pit of the opera hall, unused this evening. We wended our way through a crowd of abandoned instrument cases, and finally emerged in a small empty courtyard between new concrete and a much older part of the building.

The music was still audible, and now seemed to originate from a doorway underneath a single bulb at the other side of the courtyard. Ian was already halfway there.

So again I followed him.

We entered the doorway, and suddenly we were in the music.

Bells. Claves and snare drums, toms, crotales, ratchets, and irregular and ominous, the timpani. Brass joined, with short and loud blasts from the trombones, and quick staccato sequences from the trumpets.

Somewhere we entered another corridor. A tiled floor, whitewashed walls, polished wooden furniture, but everything covered with sand and grit. There were black and reddish brown smudges on the walls. A large potted plant had fallen over, then been pushed roughly into a corner.

The bassoons and double basses were producing a deep rumble, fluctuating in loudness and frequency. Other string players tapped an irregular col legno.

A broad trapezoid of weak daylight (daylight?) fell across the floor from behind a corner. Vague shadows moving there, almost synchronous with short, repeated motifs in the clarinets and oboes.

We stepped past the remains of the plant, avoiding a smashed chair, and peeked around the corner. At the end of the corridor was a doorway into a large room with a wooden floor. I could just see the side of a piano, and part of a high window with curtains half-drawn.

There was some movement, and the cacophonous music became louder and more insistent. The irregular drumbeats started to dominate, as all other instruments accommodated themselves to the half-formed rhythmic patterns.

And then, silence.

Seconds later: tutti, chaos, crescendo, ending on a piercing, held piccolo note.

The two Shermans are producing a dark ostinato underneath the shell bursts. The composer looks past the edge of the curtain and sees the tanks approaching along the street. “We have to get him downstairs. Where’s Yorgos?”

Eirini is sitting on her knees next to Manolis. “Searching for water. Mano’s going to dehydrate.” She wipes a hand across her brow. “We can’t move him. That would —”

A direct hit underneath the window shatters the glass. Shards rain down, tinkling against the floorboards. The composer ducks down behind the piano. “We’ll have to. We can’t leave him here.” He hears the tanks rolling to a stop. Breathless, he listens to the rumble of their engines beating against each other.

Eirini looks at him. “So close,” she whispers. Manolis groans.

The composer gets up and quickly walks towards them. “Come on. We can’t afford to wait till next year.” He squats down next to Eirini. “Mano, we’re going to get you out of here. You’re a tough one, mate. Keep it up now.” He pushes his arm underneath Manolis’ back, and pulls him carefully upright. “Now put your arm around my shoulder... nice and easy...” He motions for Eirini to support him on the other side. Slowly they get upright. When the three of them are standing next to each other against the back wall, Manolis starts to cough spasmodically. Eirini mutters a curse under her breath.

“Couplet the first, comrade Manolis,” the composer says. “The first blow is half the battle. Now for the stairs.” He moves one foot forward, nodding at Eirini. Slowly they start walking towards the door. Red foam is on Manolis’ chin.

“Couplet the second,” says the composer. “The doorstep —”

Outside: another loud boom, and from the corner of his eye he sees something black streaking through the window.

But if you hear the crash, he knows, you’ve survived it.

The room exploded.

Light, fire and smoke flung three human bodies into the corridor, against the wall. Shrapnel shot past us, burying itself in ceiling and stucco. A polytonal, multicoloured crash; a detonating cluster of wood, blood, strings and bone.

There the music ended.

In the glare of the sodium lamps, drizzle was hanging like a thin veil between the warehouse facades. Night in the city was background noise here, and a pallid glow on the clouds. Ian walked beside me, lost in thought.

“I remember now,” I said. “Xenakis was in the Greek resistance, during the war. He lost an eye to a shell fragment in his cheek. That’s why you see only half of his face in most publicity shots.”

A ship sounded its horn in the distance. I looked north, in the direction of the harbour, and saw the shadow of something dark and mountainous against the clouds.

Ian raised his head. “I have to go home.”

The light behind the windows of the warehouse was already visible at the end of the street, so I assumed that he wasn’t referring to the apartment. “Why?” I asked.

“Your music...,” he swallowed, “... is war.”

But at that moment I did not understand what he meant. I nodded, and said: “Or peace, or religion. Or love, let’s not go there.”

He shook his head. “Emotion... a baroque, decayed palace... or a battle full of... death...” He grabbed my arm. “But music is sound, air vibrations, numerical ratios. How can music be about anything?”

I stood still, wiped the water out of my eyes. My wrist was starting to hurt in his tight grip. “How?” I looked at him, then gazed into the distance. “How?” I was silent for a while. Then: “They left him for dead, you know. Because half of his face had been blown away. When his father found him, he was still breathing. But because he was a communist, he was sentenced to death. He was betrayed by his own leaders, and he fled to Paris. Nobody trusted him there, because of his disfigurement.” Ian started to turn away, but I casually put my hand on his. “He was only half of a young man. And there, he became the greatest composer of the twentieth century.”

I did not find him in my bed, the following morning. I wasn’t very surprised. A short chill, a quick touch, a blanket pulled up, is all I remember. And someone had left the kitchen window open, that morning. Classical.

Heorot remembered more. I burned a CD of his strange music: some untitled audio files and some documents full of incomprehensible calculations — the shadow of complex music, projected onto the real axis.

The program for the approximation of i is still running. I’ve tried to discover how it works. But the pain makes typing unbearable, and I don’t want to abort it. So it keeps navigating along its decision paths, day by day, forever getting closer to its result; and my nights are filled with the architecture of music. If I look out of the kitchen window, I can see a building, a palace or a temple of white marble, high on a rocky hill, above the harbour cranes in the north.

And every day the north is nearer.